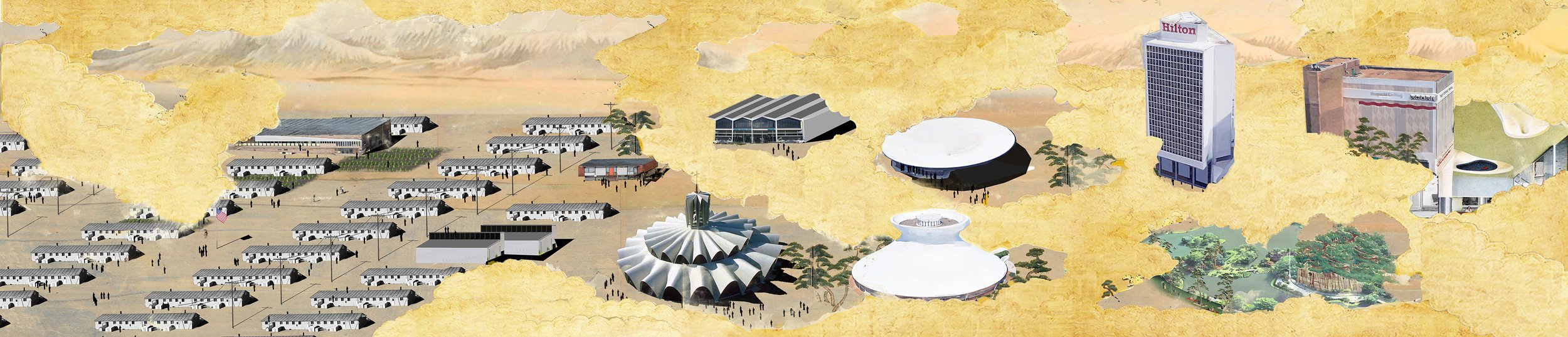

“Beauty In Enormous Bleakness” explores architecture’s relationship to issues of immigration, exclusion, and cultural identity in 20th-century America through a multi-layered investigation of the lives of Japanese-American designers/architects who survived WWII internment, and went on to make vital contributions to the post-war architecture and design landscape of the United States.

We seek to document and preserve the histories and experiences of some especially creative members of the interned generation of Japanese Americans, and in so doing, to expand the public imagination for the cultural legacies and inheritances––positive and negative––of the war. Given the ongoing efforts to “decolonize” design, and more broadly, to reckon with racial violence and white supremacy, this project writes an urgently needed new chapter in design and architectural history that acknowledges the signal contributions of Japanese Americans, Issei and Nisei alike, to post-war culture and cultural life––indeed, to the very fabric of its cities.

“If I hadn’t gone to that kind of place, I wouldn’t have realized the beauty that exists in enormous bleakness.”

--Chiharu Obata

Under the sponsorship of the American Friends Service Committee starting in 1942, The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council worked to resettle Japanese American students away from the west coast exclusion zones in a handful of midwestern colleges and universities so as to avoid internment. Among these, Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL) admitted a talented group who enrolled in several of programs of study across the university, including in the Colleges of Architecture, Engineering, and Arts & Sciences, and also the Medical School. In the years that followed, several more students found their way to WUSTL through Japanese-American networks.

Four of these students––Gyo Obata, Richard Henmi, George Matsumoto, and Fred Toguchi––went on to make vital contributions to the post-war architecture and design landscape of the United States, from residential and commercial architecture to large-scale industrial design projects to landscape architecture. Focusing on their experiences and their work, and their involvement in their communities, Beauty in Enormous Bleakness explores architecture’s relationship to issues of immigration, exclusion, and cultural identity in the 20th century, with attention in particular to the foundational effects of detention; the significance of being educatedin a midwestern city with a long history of racial tensions; the pressures of assimilation in the post-war communities where they built their careers (two of the four remaining in St. Louis for most of their lives); and their involvement in Japanese-American cultural and political advocacy.